By David Parmenter

In earlier articles I have argued, quite strongly, that the annual planning process is part of the trifecta of lost opportunities for a corporate accountant. The future is the total abandonment of the annual process as it should be replaced by a rolling quarterly, 6 quarters outlook.

But, we first need to move the annual plan into a two-week timeframe, setting the scene for the leap into the future.

There are nine foundation stones that need to be laid before we can commence a project on reducing the annual plan to two weeks.

- Separation of targets from the annual plan

- Bolt down your strategy beforehand

- Avoid monthly phasing the annual plan

- The annual plan does not give an annual entitlement to spend

- Budget committee commit to a “lock-up”

- Budget at category level rather than account code level

- Get it wrong quicker

- Build in a planning tool—not in a spreadsheet

- Plan with months that consist of 4 or 5 weeks

1. Separation of Targets from the Annual Plan

It is so important to tell management the truth rather than what they want to hear. Boards and the senior management team have often been confused between setting stretch targets and a planning process. Planning should always be related to reality. The Board may want a 20% growth in net profit, yet management may see that only 10% is achievable with existing capacity constraints.

The key is to remove any deliberate manipulation related to performance bonuses. In a working guide on ‘Designing Performance Bonus Schemes’ I point out that any performance bonuses should be paid on performance compared to the market rather than to an annual plan. We want management to be extracted from the annual charade of making a target easy so their bonus is secured.

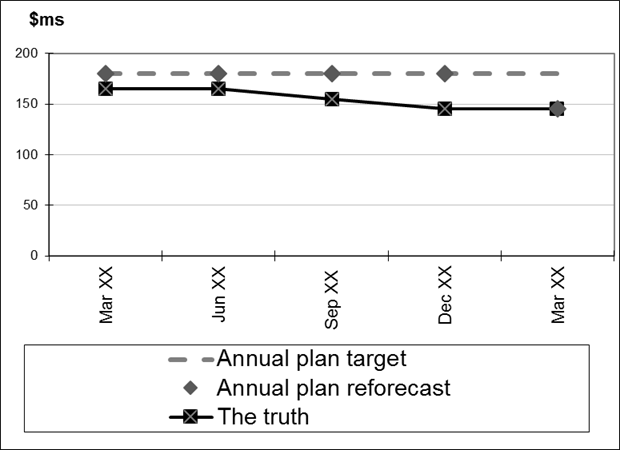

Exhibit 1 shows where management have forced the plan prepared in March to meet the target set by the Board. Each subsequent reforecast continues the charade until in the final quarter reforecast, performed in March the following year, the truth is revealed.

Exhibit 1: Reporting what the Board want to hear

2.Bolt Down Your Strategy Beforehand

Leading organizations always have a strategic workshop out of town. This session should be looked anticipated with a positive attitude. Normally Board members will be involved as their strategic vision is a valuable asset. These retreats are run by an experienced external facilitator. The key strategic assumptions are thus set before the annual planning round starts, also the Board can set out what they are expecting to see.

Great management writers, such as Jim Collins, Tom Peters, Robert Waterman, and Jack Welch, have all indicated that prominent organizations are not great because they have the largest strategic plan. In fact, it is quite the reverse; the poor-performing organizations are the ones that spend the most time in strategy and the dreaded annual planning process.

3. Avoid Monthly Phasing the Annual Budget

As accountants we like things to balance. It is neat and tidy. Thus it appeared logical to break the annual plan down in to twelve monthly breaks before the year had started. We could have been more flexible. Instead we created a reporting yardstick that undermined our value to the organization. Every month we make management, all around the organization, write variance analysis which I could do just as well from my office in New Zealand. “it is a timing difference….” “we were not expecting this to happen”, “the market conditions have changed radically since the Plan” etc.

The monthly targets should be set a quarter ahead using a quarterly rolling forecasting process. This change has a major impact on reporting. We no longer will be reporting against a monthly budget that was set, in some cases, over 12 months before the period being reviewed.

4. The Annual Plan Does Not Give an Annual Entitlement to Spend

The annual plan should not create an entitlement, it should merely be an indication, the funding being based on a quarterly rolling basis, a quarter ahead each time.

Asking budget holders what they want and then, after many arguments, giving them an ‘annual entitlement’ to funding is the worse form of management we have ever presided over.

Organisations are recognising the folly of giving a budget holder the right to spend an annual sum, while at the same time saying if you get it wrong there will be no more money. By forcing budget holders to second-guess their needs in this inflexible regime you enforce a defensive behaviour, a stock piling mentality. In other words you guarantee dysfunctional behaviour from day one!

5. Budget Committee Commits to a “Lock-up”

Most organizations have a budget committee comprising CEO, CFO, and two general managers. You need to persuade this budget committee that a three day lock-up, whereby the committee sits for up to three days, is more efficient than the current scenario that stretches over months.

During the three day lock-up each budget holder has a set time to:

- Discuss their financial and nonfinancial goals for the next year

- Justify their annual plan forecast

- Raise extra funding issues

- Raise key issues (e.g., the revenue forecast is contingent on the release to market and commissioning of products X and Y)

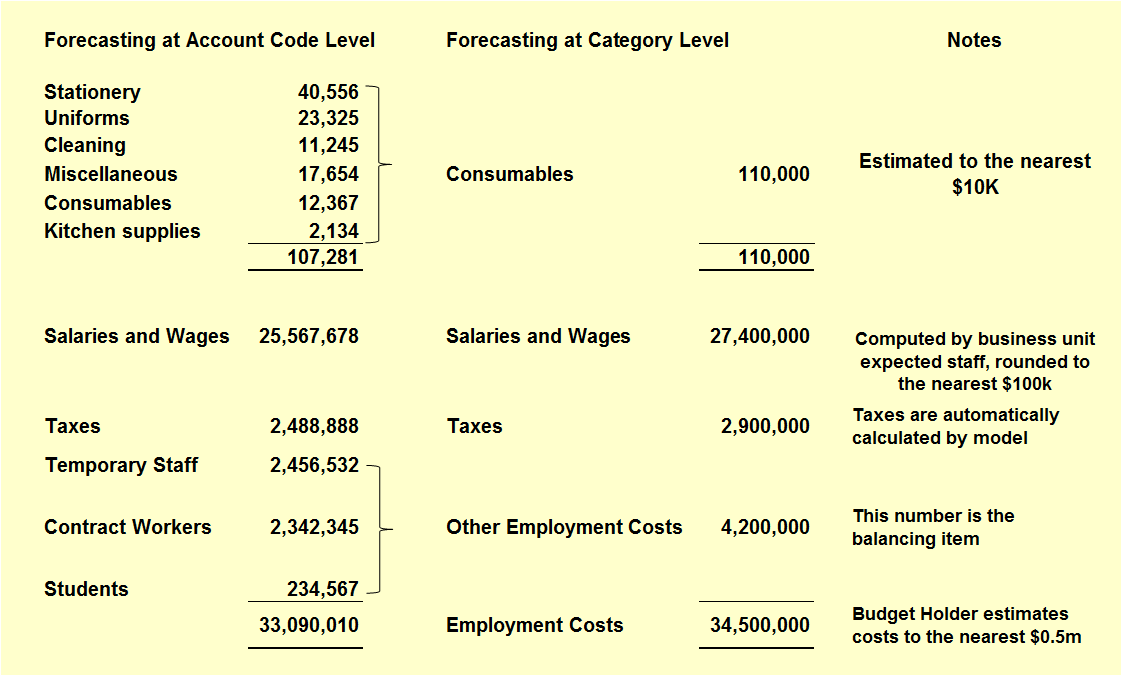

6. Budgeting at Category Level Rather Than Account Code Level

It is far better to budget at category level rather than account code level. A forecast is rarely right. Looking at detail does not help you see the future better. In fact, I would argue that it screens you from the obvious. Planning at a detailed level does not lead to a better prediction of the future. A forecast is a view of the future; it will never, can never, be right. As Carveth Read[i] said “It is better to be vaguely right than exactly wrong.” Planning a full final year in detail, in the dynamic world we live in, has always been, at best, naïve, and at worst, stupid.

[i] Carveth Read, Logic, Deductive and Inductive (1898).

Although precision is paramount when building a bridge, an annual plan need only concentrate on the key drivers and large numbers. Following this logic, it is now clear that as accountants, we never needed to set budgets at account code level. We simply do it because we did it in the previous year. You can control costs at an account code level by monitoring trend analysis of actual costs over 15 to 18 months.

We therefore apply Pareto’s 80/20 principle and establish a category heading that includes a number of general ledger codes. Helpful rules that can be used to apply this foundation stone include:

- Budget for an account code if the account is over 10 percent of total expenditure or revenue—for example, show revenue line if revenue category is over 10 percent of total revenue. If account code is under 10 percent, amalgamate it with others until you get it over 10 percent. See Exhibit 2 for an example.

- Only break this rule for those account codes that have a political sensitivity.

- Limit the categories that budget holder’s need to forecast to no more than 12.

- Select the categories that can be automated and provide these numbers.

- Map the G/L account codes to these categories—a planning tool can easily cope with this issue without the need to revisit the chart of accounts.

Exhibit 2: How Forecasting Model Consolidates Account Codes

7. Getting It Wrong Quicker

The only thing certain about an annual target is that it is certainly wrong; it is either too soft or too hard for the actual trading conditions. If we all agree that we spend months of effort getting a number wrong, then you should agree with me that we need to get it wrong quicker, but we still need a reasonable estimate.

In the past, we have given budget holders three weeks to produce their annual plan—yet they have done it all in the last day or so. They have proved to us it can be done quickly.

If we apply the foundation stones described earlier, you will have taken the politics out of annual planning—why would budget holders spend a long time fighting for an annual plan allocation if you have told them it is not an entitlement to spend?

One way to reduce the time spent in this area is to start the annual planning cycle off later. I recommend the second week of the ninth month—that is, for a December year-end, start the annual planning in week 2 in September.

The CEO needs to make a fast time frame non-negotiable in all communication with staff. As long as the foundation stones are in place and the CEO has agreed to get behind a fast annual planning process

8. Built in a Planning Application – Not in Spreadsheets

Spreadsheets have no place in forecasting, budgeting, and many other core financial routines. Spreadsheets were not designed for many of the tasks they are currently used to accomplish. In fact, at workshops I often remark in jest that many people, if they worked at NASA, would try to use Microsoft Excel for the US space program, and many would believe that it would be appropriate to do so.

A spreadsheet is a great tool for creating static graphs for a report or designing and testing a reporting template. It is not, and never should have been, a building block for your company’s finance systems. Two accounting firms have pointed out that there is approximately a 90 percent chance of a logic error for every 150 rows in an Excel workbook.[i]

[i] Coopers and Lybrand found 90 percent of all spreadsheets composed of more than 150 rows contained errors (Journal of Accountancy, “How to Make Spreadsheets Error-Proof”) and KPMG found 91 percent of 22 spreadsheets taken from an industry sample contained errors (KPMG Management Consulting, “Supporting the Decision Maker: A Guide to the Value of Business Modelling”).

9. Plan with Periods that Consist of 4 or 5 Weeks

The calendar in use today can be a major hindrance in forecasting. With the weekdays and number of weekend days, in any given month, being different from the next month, forecasting and reporting can be unnecessarily compromised. Closing off the month on a weekend can make a big positive impact in all sectors.

Forecasting models should be based on a “4, 4, 5 quarter”; that is, two four-week months and one five-week month are in each quarter, regardless of whether the monthly reporting has moved over to this regime. Calculating and forecasting the following items then becomes easier:

- For retail, you either have four or five complete weekends (the high-revenue days).

- You have either four weeks of salary or five weeks of salary.

- Power, telecommunications, and property-related costs. These can be automated and be much more accurate than a monthly allocation.

- Monthly targets. You can simply adjust back based on calendar or working days.

Simply design the model so that smoothing back to the regular calendar can be removed easily when you decided to migrate reporting to 4- or 5-week months.

To make progress in this area, I recommend to that you contact your general ledger supplier and ask, “Who is a very sophisticated user of this general ledger and who uses 4, 4, 5 reporting months?” Arrange to visit them and see how it works for them. Ask them, “Would you go back to regular calendar reporting?” Most are likely to give you a look that says, “Are you crazy?”

Next steps

- Buy my toolkit which is on sale (over 40% discount) “An Annual Plan in Two Weeks or Less Toolkit (Whitepaper + e-templates). You can look inside the toolkit

- View this YouTube Beyond Budgeting – an agile management model for new business and people – Bjarte Bogsne, at USI

- Read:

https://review.firstround.com/Annual-Planning-is-Killing-Your-Growth-Try-This-Instead

https://hbr.org/2006/01/stop-making-plans-start-making-decisions

https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/finance/beyond-budgeting/